Blog

The Impact of COVID-19 on Schools and Out-of-School Time Programs

How to Build Strong Relationships in a Changing World

It’s tough to overstate the impact of COVID-19 on the relationships between teachers, staff, and leaders, and young people in schools and out-of-school time (OST) programs. The pandemic upended life as we knew it, and we’ve had to rethink everything: how we communicate, how we educate, and how we connect and form relationships.

The year-plus since the pandemic hit has taken an enormous social, psychological, and emotional toll not only in terms of lost learning but also lost connection for so many adults and youth. While these losses are felt by almost everyone, they are disproportionately felt along racial, ethnic, and groups from low-income backgrounds.

As the new school year begins, the relational, learning and developmental challenges of the COVID-19 pandemic and its unequal impact continue to disrupt school and OST programs. Leaders widely recognize the need to address the stress and trauma that youth and practitioners have experienced as a result of the pandemic. And yet, many feel they lack the strong relationships and the skills in trauma-informed care required to address these needs.

How do teachers and OST staff build from this unstable foundation to form meaningful developmental relationships with young people and their families?

That is the question we sought to answer when we gathered data from teachers, staff, and leaders as part of a Minnesota case study of schools and OST programs; drawing on surveys, focus groups, and interview data to provide a state-level illustration of those national trends that show the impact of COVID-19 on the relationships that we know are critical to young people’s development.

The Impact of COVID-19 on Relationships in Schools and Out-of-School Time Programs

“My experience with relationships with youth during the pandemic was mixed. Some students flourished on Zoom. They loved being able to share with me [through chat] without actually having to talk. On the flip side, it was very awkward to try to build relationships and have students open up when they were at home with their parents. That made it super awkward and uncomfortable. The setting got in the way.”

—Out-of-school program practitioner, Greater Minnesota

With data collected between February and June 2021 from a diverse sample of 668 schools and OST leaders and practitioners serving a wide range of young people across the state, the Minnesota case study provides a snapshot of what school and OST staff (i.e., teachers, staff, leaders) have experienced during the pandemic as they seek to develop and sustain relationships. Here is what we found:

-

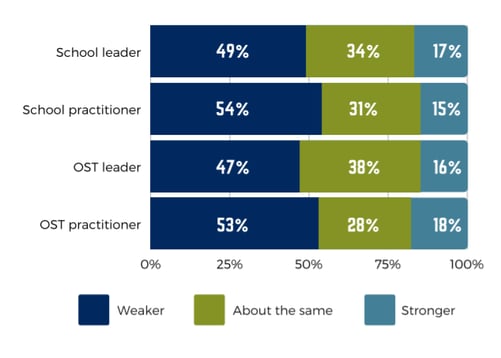

Most school and OST staff reported having positive relationships with youth. But about half reported that those relationships have weakened during the COVID-19 pandemic; despite staff reporting being more intentional about maintaining relationships with youth during this same timeframe.

-

School staff, and to a lesser extent OST staff, saw their schools and programs as responsible for helping youth navigate trauma-related challenges. Yet, most staff saw their schools and programs as being only somewhat effective in helping youth navigate the challenges related to trauma.

-

Staff ranged in how competent they felt using trauma-informed practices. Staff felt most competent in understanding how trauma can impact youths’ relationships while feeling least competent at identifying the signs of trauma in youth.

-

Although most staff reported that they have connections to external resources (i.e., outside their schools or programs) that are trauma-related, they reported lower internal capacity (i.e., within their schools or programs) to identify and support youth and staff who have experienced trauma.

The data provide insights into how school and OST staff perceived changes in their relationships with youth and families. Furthermore, the findings show that many school and OST leaders and practitioners feel that their relationship-building efforts need to address the trauma that young people have experienced during these challenging times — and that they have experienced in general. In other words, building strong relationships with young people requires trauma-informed care and spaces to support them.

Shifting Relationships

There’s no doubt that COVID-19 has had an impact on relationships.

A majority of school and OST staff reported that they have positive relationships with the youth in their school or program. However, the pandemic weakened many of these relationships. This was particularly true for practitioners who likely experienced the greatest day-to-day shift in how they interacted with the youth. Practitioners found that some youth continued to engage, learn, and develop in the unfamiliar environments caused by COVID-19 (e.g., social distancing, closures, mask-wearing), while other youth struggled to get their bearings.

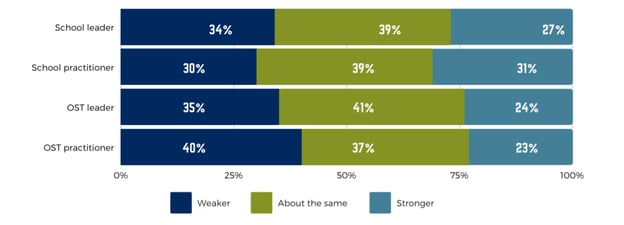

When it came to relationships with families, the results were mixed. Again, most of the participants reported that they had positive relationships with the families of the youth they serve. But when asked about the effect of the pandemic on their relationships, they were almost evenly split on whether those positive relationships had weakened, stayed the same, or grew stronger. Interestingly, 31% of school staff reported that relationships with families had improved during the pandemic.

Recognizing the importance of supporting youth throughout the COVID-19 pandemic, school and OST staff tried to adjust their methods and approaches to find ways to connect with youth, for example, by:

-

Providing training to school and OST practitioners on how to build relationships with youth during the pandemic.

-

Checking in with youth during weekly/monthly meetings.

-

Reaching out to youth and families through different media.

-

Offering explicit opportunities for youth to develop social and emotional competencies (e.g., self-awareness, relationship-building skills, self-management).

These adjustments were essential for building and reinforcing positive staff-youth relationships.

Trauma-Informed Relationship Building

“The trauma that has occurred within this last year is huge. Every person has had a different experience with this pandemic, which makes it very difficult to do [social and emotional learning] that works for every student. Where the school may have had a positive and successful program in the past, it likely is not working right now. When we add in the struggles with food insecurity, poor internet, no computer usage, etc. along with a huge number of deaths and personal fear, it is difficult to know where to start.”

—School Leader, Twin Cities Metro

The COVID-19 pandemic was a traumatic event. It upended the ways we formed relationships, as social distancing mandates and in-person school closures limited interactions. Normal routines were interrupted, and life celebrations, like weddings, graduations, and birthdays, were limited. These changes caused additional strain on youth and adult mental well-being.

The changes were profound. Students lost family members and loved ones. Families lost jobs and income, and food insecurity skyrocketed. It’s no wonder it became difficult for many to focus on online school.

As society moves toward reopening, adults will need to be intentional about re-developing positive relationships with youth. That means creating trauma-informed spaces for healing and nurturing relationships.

Trauma-informed Spaces

Trauma-informed spaces are physical spaces that promote safety, well-being, and healing by attending to trauma-informed principles such as peer support and youth empowerment. The need for trauma-informed spaces in education settings, such as schools and OST programs, is essential following the COVID-19 pandemic.

However, not every participant in the study felt equipped to recognize and support students in trauma-informed spaces. School leaders were more likely to report that they realized trauma’s impacts and recognized when young people are experiencing trauma.

A clear need exists for more training and resources to adapt educational settings to be trauma-informed spaces.

Whose Responsibility?

A majority of school leaders (90%) and staff (84%) in the study agreed that their schools are responsible for helping young people navigate the challenges related to trauma. Meanwhile, fewer OST leaders and staff agreed or strongly agreed that their program was responsible for helping youth navigate the challenges of trauma.

Taking Action for the Future

As schools and programs adjust to the 2021-2022 school year, intentionally building, and in some cases re-building, relationships with youth must be at the center of the efforts. But being intentional won’t be enough, it will require increased attention to the ways in which staff support youth in navigating stress and trauma.

Staff and leaders in the Minnesota study shared the following strategies as possible pathways for building intentional relationships in trauma-informed spaces as they get ready for the new school year:

-

Place relationship-building at the center of every interaction. School and OST staff can spend more time intentionally building relationships where every interaction with young people provides an opportunity to get to know them better, understand what excites them, and help them navigate challenges. Some examples include activities that allow students and staff to collaborate, personalized learning opportunities within lessons, and regular one-on-one check-in meetings with each youth.

-

Offer on-site mental health resources for adults and youth. Increase support for processing and healing, providing access to professional development opportunities on creating trauma-informed spaces, reflection time during activities, and on-site mental health counselors for young people and adults.

-

Use technology to support youth in navigating stress and trauma. Find new and innovative ways to connect with youth. Many schools and programs are turning to online apps to support adults and youth in building their social and emotional competencies, identifying signs of trauma, and navigating stress and trauma.

-

Tailor relationships to young people’s unique needs. Leaders and practitioners must differentiate the ways they build relationships, and commit to helping every young person form at least one positive relationship in their school or program.

-

Change schools and OST programs to better serve youth. Due to the pandemic, youth need more individualized support to help them navigate stress, trauma, and learning. For example, reducing the number of students in classrooms and programs, creating flexible learning schedules, and connecting more directly with families in homes and communities.

As we continue to grapple with the lasting impacts of the pandemic, the insights gleaned from the staff and leaders in Minnesota offer a blueprint for moving forward with clear needs to meet in order to support young people in navigating the stress and trauma of the COVID-19 pandemic. Supporting schools and OST staff in building intentional relationships and creating trauma-informed spaces will - without question - be essential during the 2021-2022 school year.

The complete study can be found in the Search Institute Insights & Evidence brief titled Building Relationships and Addressing Trauma During the COVID-19 Pandemic.