Blog

Solving America’s Crisis of Academic Motivation

By: Kent Pekel, Ed.D., President and CEO

A decade ago, the National Research Council released a report that showed that between 40 and 60 percent of U.S. high school students are disengaged from learning and don’t put much effort into school. Since that time, other studies have found that student motivation is a problem at all levels of the educational system, and that students’ desire to learn decreases steadily from the start of elementary school until they graduate from high school or dropout. On a recent national survey, 69 percent of teachers reported that low academic motivation is a problem in their classrooms—a higher percentage than cited poor student behavior, bullying, or a negative school climate.

Rising awareness of this crisis has helped to fuel growing interest in research on motivation among America’s educators, staff at academically-focused youth programs, and millions of parents. Across the country, people are reading books and watching TED Talks in which psychologists and other scholars describe ways to help students adopt growth mindsets, increase grit, achieve goals, and envision their future possible selves.

In my view, this attention is a very good thing. It is helping reduce the fever that gripped the country during the worst days of the standardized testing movement, when we deluded ourselves into thinking that if we just raised academic standards, America’s most struggling students would respond with the increased effort required to meet them.

But as is often the case, progress has presented a new problem. Each researcher whose work is getting well-deserved attention has focused on a single, important aspect of student motivation. For instance, Carol Dweck of Stanford University has explored the impact of a growth mindset, while Angela Duckworth of the University of Pennsylvania has examined grit—to highlight just two of the most prominent scholars today.

However, teachers and other educators who work directly with students struggle to know when and how to apply these different approaches to the complex and diverse motivational challenges they encounter in the classroom. For example, one student may not work hard in school because she believes she doesn’t belong there. Another student might not work hard because he sees little connection between school and the things he is interested in and loves to do.

That’s why we need a broader framework that helps educators organize and connect the dots between these distinct bodies of research on motivation—and the interlocking challenges they each address. Toward that end, over the past two years my colleagues and I at Search Institute have developed a new framework for strengthening students’ desire to work hard in school. We are now testing interventions organized around our framework in a diverse group of middle schools and we will report on the outcomes we achieve over the next two years.

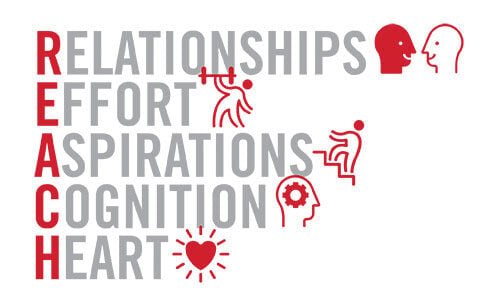

In the meantime, we thought it would be helpful to share our framework with others who are also working to enhance academic motivation. It has five components, each of which is summarized by a letter in the acronym REACH:

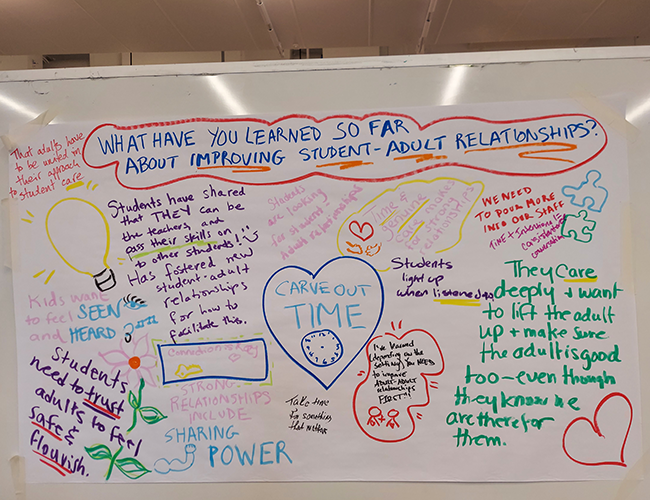

Relationships: The single most powerful thing that educators can do to increase motivation is to build close connections with their students. Ongoing research we are conducting at Search Institute is finding that those close connections become truly developmental for young people when five elements occur regularly and authentically in the relationship: expressing care, challenging growth, providing support, sharing power, and expanding possibilities.

Effort: Adults also need to help students believe that when they challenge themselves mentally, use good learning strategies, and see mistakes and failures as opportunities to improve, they can become smarter and more successful in school.

Aspirations: If we help students develop positive visions of their possible selves and see how their actions in the present will affect their ability to realize those visions, we can improve both academic effort and academic outcomes.

Cognition: When we teach students to think about their own thinking, it strengthens their ability to manage learning and control impulses. Those skills, in turn, strengthen students’ abilities to complete tasks and achieve goals.

Heart: Educators can support students’ intrinsic motivation by helping them discover and reflect on what they love to do (their sparks) and what they love about themselves (their best values). When students see their own strengths and when educators acknowledge those strengths, students are better able to resist biases such as stereotype threat and achieve their full potential in school.

At Search Institute, we have recently begun surveying students to measure the degree to which they demonstrate and experience each component of the REACH Framework. Among other things, we are finding that there are simple but potentially powerful things that schools can do to increase motivation in each category of the framework.

For example, data on the Heart component shows that many schools could do a much better job of knowing students’ deep interests and talents—what we call sparks—and integrating them into the curriculum and into informal conversations with students. In one diverse high school that we surveyed, for instance, 81 percent of the students reported that they have such sparks in their lives, and 63 percent reported that successfully developing their sparks gave them confidence they could tackle other hard challenges. In that same school, however, 50 percent of the students reported that teachers don’t try to connect what they are learning in class to their sparks, and 43 percent reported that their teachers don’t try to find out what they are interested in.

For more than a quarter century, Search Institute has used conceptual frameworks like REACH to help adults who work with young people understand, organize, and apply findings from complex and sometimes contradictory bodies of research. A good framework helps people focus on what matters but doesn’t mandate a particular curriculum or approach. It creates the space in which educators and others who work on the front lines with young people can join our best researchers in finding solutions to the motivational crisis that keeps far too many students from becoming all that they can be in school and in life.